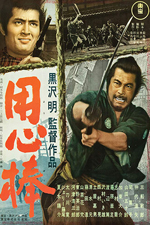

Released: 1961

Released: 1961

Starring: Toshiro Mifune, Tatsuya Nakadai, Yoko Tsukasa, Isuzu Yamada, Daisuke Katō, Takashi Shimura, Kamatari Fujiwara, Atsushi Watanabe

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Distributed by: Toho

Rating: Not Rated

“Better if all these men were dead. Think about it!”

A wandering warrior for hire winds up in a town caught in a crossfire between two rival gangs of marauding bandits. The nameless wanderer soon sells his services to both sides playing them against one another to save the townsfolk… and make a handsome amount of money in the process.

I know what your thinking, “Wait, I’ve seen that movie! It stars Clint Eastwood and it’s directed by Sergio Leone” Well you are half right, I didn’t, however, have some form of stroke and place the wrong name in the header. Yojimbo is one of the most popular samurai movies ever made by Akira Kurosawa the legendary director who greatly influenced the likes of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. He also inspired Sergio Leone, who adapted Kurosawa’s film into a western. Which got him rightfully sued by Kurosawa’s people and Kurosawa even sent him a letter stating that it “…was a fantastic film. Unfortunately, it is my film.” Which is flattery on both sides.

But I’m sure you didn’t open this review to hear me wax on about the fraternization of directors. Yojimbo is a black and white tale of a wandering ronin (a samurai who has failed his duty to protect his master, but refused the act of seppuku to follow his master to the next life and instead wanders the land selling his sword for a bowl of rice) who happens upon a town with the only two people making an honest living, are the general store owner and the coffin maker.

The nameless swordsman (Toshiro Mifune; Rashomon, Seven Samurai) is a complex character with enough rounded characterization to make him extremely likable, possessing a fierce honour and loyalty, his emotions hidden but still bubbling at the seams, and with a carefree reckless sense of humour. Later, we seemingly find out his name is Sanjuro Kuwabatake which translates to “30-year-old mulberry field”, an obviously improvised name. Sanjuro meets quickly with an old man who is bitter at the samurai for having no honour and just being another murderer in the unnamed town.

Sanjuro meets both sides of the warring town. Both without any real ideas of what they fight for except ownership of the town. Sanjuro toys with and plays both sides against one another. Even going as far as to be hired by one gang only to decide right before both gangs clash in the center of the town that he won’t work for them, returns the money he was paid, and takes perch upon a lookout tower laughing as the bandits fail to actually fight and instead run around like confused children.

At the midpoint of the film Ushitora’s youngest brother Unosuke (Tatsuya Nakadai; Ran, Harakiri) returns from his travels bearing a firearm. The brother has his suspicions about Sanjuro and eventually catches Sanjuro helping the townsfolk. He sets the town into chaos and Sanjuro on a revenge path.

Sanjuro as a character may be the original badass with a heart of gold, the rugged man’s man archetype. To think that Clint Eastwood made his career off the imitation of this man is sentiment to Mifune’s capability as an actor. He starred in films from 1947 up until 1995 almost consistently working every year. He worked hard and how he worked is more essential than what he worked on.

Toshiro Mifune studied the craft of acting without the pompous nature of western theatre. No, Toshiro instead studied animals. For instance, a lion and how it would walk among its pride and stare down its enemies. During a particular scene, the protagonist is surrounded by bandits massively outnumbering him. He doesn’t back down, but rather talks to them, hearing them speak of how tough they are and their capabilities as warriors. Sanjuro walks the circle they made. Proud and getting right into their faces sizing them up as would a lion. He then strokes his beard, tells them he is now going to kill them, and attacks all of them in the blink of an eye. No slow motion, no nifty camera work, just speed and aggression taking them apart limb from limb till the remaining opponents run scared.

Sanjuro looks down at the bandits and thugs of the town. Constantly switching sides and letting them show their weaknesses like a cat toying with a mouse, finding it entertaining how it thrashes before it’s doom. It’s this direction by Akira Kurosawa and acting by Toshiro Mifune that makes Yojimbo so entertaining and magical to watch. Kurosawa frames the actors with beautiful camera work with each scene becoming a painting foreshadowing what is about to happen, and when it’s executed by Mifune, it’s almost like ballet. The composition of movement that Mifune brings, combined with the camera work and direction of Kurosawa make this a beautiful film you have to see move.

The extended cast in Yojimbo are hit and miss. There is a litany of humourous and more serious recurring characters of either side of the war. Whether deliberate or not, trying to remember who is on whose side is quite confusing due to the black and white footage and the language barrier of subtitles, but the film continues as if it expects you to know. This can be forgiven as Yojimbo was indeed intended for an Eastern audience.

The old man character acts almost as the audience’s proxy. Constantly berating the violent actions of Sanjuro. Wondering constantly what Sanjuro’s endeavours are for? His own gain or the safety of the townsfolk?

Unosuke, the villain, is a tender young man with violent tendencies and a pistol. In 19th century Japan, a firearm is a massive boon against men carrying swords, and also a deeper insight into violence. Yojimbo was a commentary on modern violence depicted in film, showing the more lasting effects of violent actions.

The pistol itself is almost representative of the loss of honour among warriors. While the katana is used, it is a more honourable form of violence, making the battlefield equal only to the combatants’ skill. The pistol, in almost every scene, is framed as a sneaky weapon applied by cowards. The villain is contrasted against Sanjuro. Unosuke is the polar opposite in almost every way. He is lacking in any formal honour, violent, brash, and quick to act, also young. Unosuke makes for an interesting villain and it is a pity he is introduced quite late into the film (50 Minutes). More time spent watching Sanjuro and Unosuke facing off each other would have been greatly welcomed.

The set and sound design work to bring a very remote sense of isolation and an impoverished desolate land, making Yojimbo seem dream-like in some sense. The only sense of law and order amidst all the chaos is Sanjuro himself. Bandits run amuck doing as they please in the town. The Japanese backdrop is very believable as the black and white starkness hide anything that would give the modernization away.

The monochrome aesthetic is beneficial to the film along with the soundtrack which in itself is quite inert. This isn’t bad for the film as the musical tracks within it are very unique for the genre. However, the large majority of the film itself is silent with only the droning wind making any kind of sound.

Overall the film is very enjoyable, but its age does not serve it well in certain aspects — such as thugs getting slashed with katanas, but not a drop of blood to be seen. The long length of the film is filled with fantastic scenes and acting, but hampered by exposition. If someone was a patient viewer with an enjoyment of eastern film, they would indeed find Yojimbo to be entertaining and an essential watch, but for a casual viewer this may be harder to sit through as the language and age of the film may tire a viewer out.

Rating:

Thomas C:

Leave a Reply